concerning the biological components of facial expression

It seems natural for people to make facial expressions, yet it also seems that we learn them from one another. In what ways are facial expressions a function of one's biological makeup?

There is no denying that biology has a great deal to do with the facial expressions that people make. Our common sense seems to tell us that the faces we make are natural; we don't smile when we are happy or frown when we are sad because we saw someone else do this movement at some time in our past, we smile or frown because we feel like it. But since common sense can from time to time be misleading in areas of scientific investigation, countless studies and experiments have also been conducted that have served to support the idea that there is something ingrained in our human genome that causes us to make faces in certain situations.

One main area that has been studied is the facial expressions that babies make. Young babies have had only a short amount of time to learn habits from those caring for them, so therefore their actions are representative of the natural, predisposed facial inclinations with which all people are born. D. S. Messinger, A. Fogel, and K. L. Dickson are three of the numerous researchers who have turned to infants in search of answers to uncertainties about facial expressions. They observed the different occurences of babies making Duchenne smiles (where the muscles around the eyes are contracted in addition to the sides of the mouth being turned up) with the occurence of "play" smiles (where the eye muscles aren't contracted and the babies' mouths are slightly open). They found strong correlations between the type of smile made and the context in which the baby was smiling. Most of the time, babies would make Duchenne smiles during "positive interactive events" and play smiles during interaction involving actual physical contact (Messinger). The fact that babies make the same sorts of faces as each other in the same types of situations seems to be strong evidence supporting the idea that humans are biologically inclined to move certain muscles in our faces in similar, specific ways.

One main area that has been studied is the facial expressions that babies make. Young babies have had only a short amount of time to learn habits from those caring for them, so therefore their actions are representative of the natural, predisposed facial inclinations with which all people are born. D. S. Messinger, A. Fogel, and K. L. Dickson are three of the numerous researchers who have turned to infants in search of answers to uncertainties about facial expressions. They observed the different occurences of babies making Duchenne smiles (where the muscles around the eyes are contracted in addition to the sides of the mouth being turned up) with the occurence of "play" smiles (where the eye muscles aren't contracted and the babies' mouths are slightly open). They found strong correlations between the type of smile made and the context in which the baby was smiling. Most of the time, babies would make Duchenne smiles during "positive interactive events" and play smiles during interaction involving actual physical contact (Messinger). The fact that babies make the same sorts of faces as each other in the same types of situations seems to be strong evidence supporting the idea that humans are biologically inclined to move certain muscles in our faces in similar, specific ways.

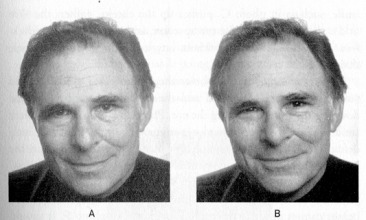

Here is an example of someone making a Duchenne smile (right) as opposed to a "false" or "social" smile (left). This second type of smile is somewhat different from the "play smile" identified by Messinger, Fogel, and Dickson in babies. But regardless of the name given for this type of facial movement, these distinct types of smiles are something that all people exhibit. Furthermore, people exhibit them in similar circumstances. The fact that this subtle aspect of facial expression is found in practically every person certainly says something about the universality and the inherent aspect of facial expressions.

Similarly, researchers have been interested in observing the types of faces that blind people make, since those blind from birth are clearly unable to learn what sorts of faces to make from other people. Researchers David Matsumoto and Bob Willingham observed the facial expressions made by people who were congenitally and noncongenitally blind in the 2004 Paralympics. The somewhat surprising results suggested that there was little or no difference between the facial expressions made by those who were congenitally blind, noncongenitally blind, and those who were able to see. Also, no variation was found between cultures with regards to facial expressions (Matsumoto "Spontaneous"). This is more evidence in support of the idea that facial expression does not rely on what one learns from cultural or societal interactions; this seems to suggest that facial expressions are more of an innate tendency.

This image was shown in an MSNBC article that discussed the implications of Matsumoto and Willingham's study. These are both athletes who just lost a match for a medal. The one on the left is blind, and the one on the right has sight. Clearly, the faces they are making are very similar: both have the ends of their mouths turned down and the inside of their eyebrows raised up.

In a similar study, Irenaus Eibl-Eibesfeldt observed the facial patterns of children who were born deaf and blind. His results were similar to those mentioned above: he found that "deaf and blind children smile when the mother caresses them; they laugh during play, cry when they hurt themselves, and emit all the appropriate sounds while doing so. When angry, they frown and clench their teeth. They even stamp their feet in rage, just like any angry person would do" (Eibl-Ebesfeldt, 30-31). Once again, the commonalities between blind and sighted people suggests that facial expression is not something that has to be learned by observing other people.

Does the fact that there is a strong biological component of facial expression indicate that facial expressions are universal?

Especially in the earlier history of the study of facial expressions, people tended to believe that they were largely, if not completely, universal in nature. In 1872, Charles Darwin published a book on the subject called The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. In this book, Darwin assumes that facial expressions are universal; he also asserts that because of this, they must be inherited. Darwin's work was largely forgotten until the second half of the twentieth century, when the idea of universality was again brought to the forefront of academic debate and research. Some scientists, such as Otto Klineberg, Ray Birdwhistell, and Weston Labarre, did not accept Darwin's idea that facial expressions were universal. But others did formulate ideas that supported Darwin's idea of universality, bolstering it with better scientific methods and experiments (Ekman).

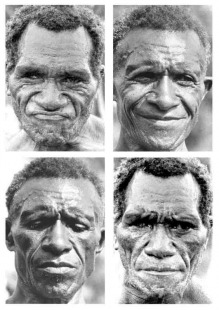

Historically, Paul Ekman has been a major supporter of the idea that facial expressions are universal. In the 1980's, he and his colleagues Carroll Izard and Wallace Friesen developed a set of assumptions and theories about facial expressions in their "Facial Expression Program". Ekman conducted studies in various cultures that involved, among other things, taking pictures of different people making different faces and asking people from the different cultures to identify which emotion they thought was reflected in a picture of a person smiling, frowning, etc. This research led to the distinct Facial Expression Program that was based on the universality of facial expression. This program holds there there are between five and nine distinct, universal, and genetically determined emotional states. Each one corresponds to a certain facial expression, certain feelings, and certain physiological components that characterize it. The production and recognition of these emotions is an innate ability (as opposed to something that is learned from one's culture) (Ekman, Russell). This program was adopted for a long time; it was cited by various scientists from all sorts of disciplines, was adopted by college textbooks, and was presented to the public as the prevailing view on the subject.

However, people have been wary of the confidence with which Ekman makes his claims about universality. Today, hardly anyone would assert that every aspect of his Facial Expression Program is true. As time has gone on since his ideas were first published in the 1980's, more forgiving systems of ideas about the universality of facial expression have been developed. These newer systems acknowledge the universal aspects of facial expression while also admitting that there are cultural influences that differentiate facial expressions across cultures. One such system is the system of Minimal Universality. This system asserts that there are certain facial movements that all people make, that there are certain psychological components associated with these faces, and that most people everywhere are able to receive some sort of information from the person making a certain face. However, this system also warns that facial actions aren't necessarily signals nor are they necessarily linked with emotion. Also, Minimal Universality proposes that facial expressions are not necessarily interpreted in the same way by different individuals or by people in different cultures (Russell).

Historically, Paul Ekman has been a major supporter of the idea that facial expressions are universal. In the 1980's, he and his colleagues Carroll Izard and Wallace Friesen developed a set of assumptions and theories about facial expressions in their "Facial Expression Program". Ekman conducted studies in various cultures that involved, among other things, taking pictures of different people making different faces and asking people from the different cultures to identify which emotion they thought was reflected in a picture of a person smiling, frowning, etc. This research led to the distinct Facial Expression Program that was based on the universality of facial expression. This program holds there there are between five and nine distinct, universal, and genetically determined emotional states. Each one corresponds to a certain facial expression, certain feelings, and certain physiological components that characterize it. The production and recognition of these emotions is an innate ability (as opposed to something that is learned from one's culture) (Ekman, Russell). This program was adopted for a long time; it was cited by various scientists from all sorts of disciplines, was adopted by college textbooks, and was presented to the public as the prevailing view on the subject.

However, people have been wary of the confidence with which Ekman makes his claims about universality. Today, hardly anyone would assert that every aspect of his Facial Expression Program is true. As time has gone on since his ideas were first published in the 1980's, more forgiving systems of ideas about the universality of facial expression have been developed. These newer systems acknowledge the universal aspects of facial expression while also admitting that there are cultural influences that differentiate facial expressions across cultures. One such system is the system of Minimal Universality. This system asserts that there are certain facial movements that all people make, that there are certain psychological components associated with these faces, and that most people everywhere are able to receive some sort of information from the person making a certain face. However, this system also warns that facial actions aren't necessarily signals nor are they necessarily linked with emotion. Also, Minimal Universality proposes that facial expressions are not necessarily interpreted in the same way by different individuals or by people in different cultures (Russell).